THE FINAL DAY

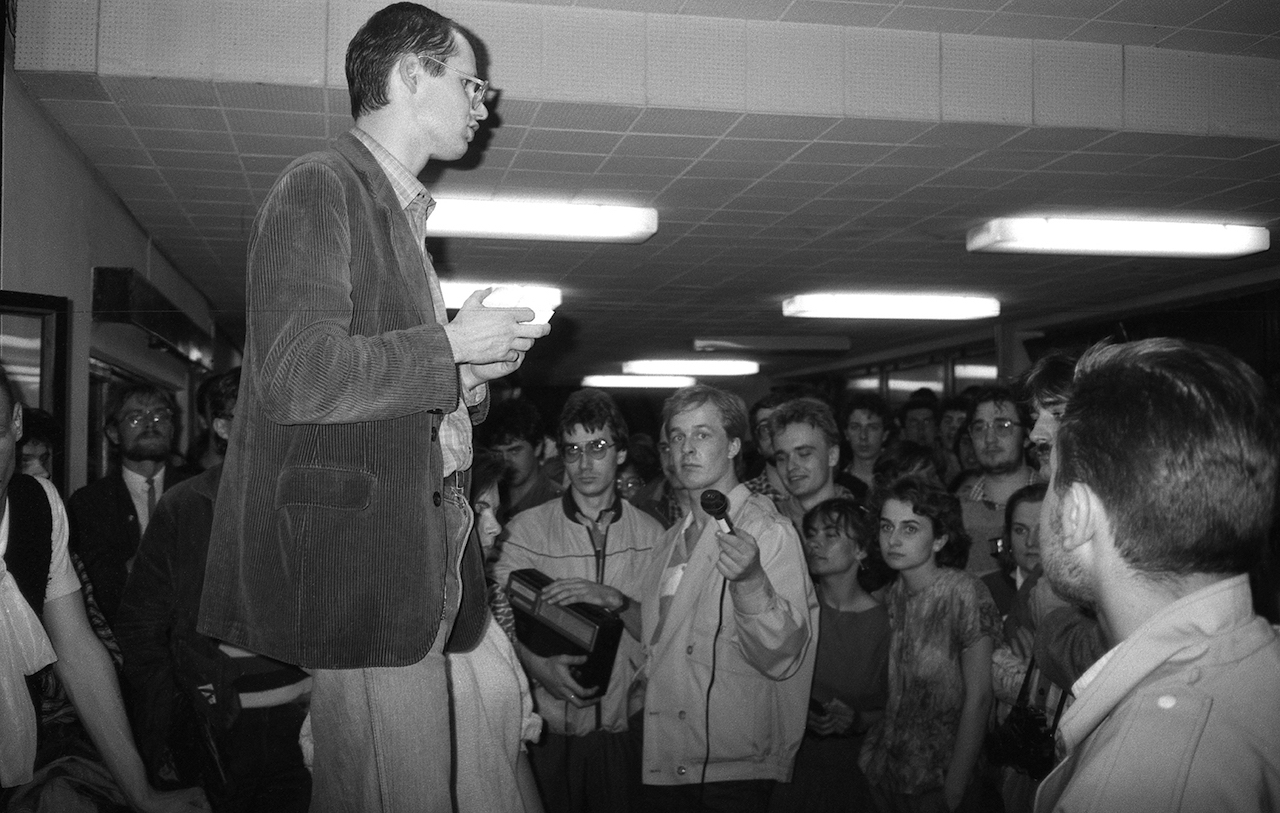

Sunday, 13 January 2019, was rather warm for the middle of winter. Adamowicz put on a light coat. He was to return home to Jelitkowo late in the evening, after the finale of the Great Orchestra of Christmas Charity. Before noon he went to the nearby Church of SS. Peter and Paul. Then he paid a visit to his parents at the family home in Mniszki St. It was a block of flats dating back to the late 60s: stairs, first floor, door, all of which he had known forever. He said that he didn’t feel well, that he had slept badly, that he had nightmares. His parents replied that he should take a nap. His 90-year-old father laid him to bed and covered him with a duvet. When he woke up, the Mayor had lunch. Then he said goodbye. Around 13:45, he went in front of the house, where an assistant joined him on the street. Together, they went to the Long Market by the Fountain of Neptune. Almost a kilometre by foot. There, the Mayor was to be interviewed about Prelate Jankowski for German television. They asked what would become of the priest’s statue, what was the atmosphere in the city in light of the accusations that the priest, who had been dead for years, was a paedophile, a cause of human tragedies. Right after that came another interview on a more pleasant subject, about the finale of the 27th Great Orchestra of Christmas Charity. The Mayor began collecting later than he had announced, not at noon but about at 14:10. He carried his collection box with a red lanyard labelled “I’m From Gdańsk” on his neck with a volunteer’s ID. People were eager to put money in the Mayor’s box. Every now and then, someone would want to talk to him, shake his hand, take a selfie with him. They said they had voted for him in the recent election and were happy because he governed the city well. Right after 16:00, Paweł Adamowicz entered the Armoury building, which was the usual HQ of the Gdańsk finale of the Great Orchestra of Christmas Charity. The assistant asked the Mayor whether he would like a roll to eat. With his typical sense of humour, Paweł Adamowicz replied, “No, it’s too fattening,” and then asked for a jelly doughnut and ate it. A moment later, the counting of the money from the Mayor’s box began. There were 5613 zloties and 11 groszy in it. Adamowicz beamed with delight; he had made a new personal record in collecting for the Great Orchestra of Christmas Charity. Just before 17:00, the Mayor took a slice of pizza and went for some pierogis at the restaurant of city councillor Piotr Dzik in Piwna St. By about 17:45; he was at the District Court building, where there was to be a demonstration in defence of the constitution and the independence of the Polish judiciary. Fifty of the most tenacious opponents of the methods used by the governing PiS Party were gathered there. Adamowicz spoke about the need to protect the courts and democratic values.

In parting, he heard, “See you on Monday, Mr Mayor,” because the next day he was to read parts of “On Tyranny” by Timothy Snyder at a public meeting at Oliwa Culture City Hall.

At 18:30, the Mayor of Gdańsk returned to the Coal Market, the square where the events that accompanied the Gdańsk finale of the Great Orchestra of Christmas Charity were held. With three associates, he went into a bar next to Wybrzeże Theatre to get warm and get on stage before 20:00, when the closing ceremony was to begin. The Mayor insisted that they all read more newspapers to know where the country was going. At 19:50, they went on stage. Everyone awaited the Light to Heaven, the celebration to end the Great Orchestra of Christmas Charity finale. The Mayor’s assistant took a souvenir photograph of him with a sparkler in hand. A moment later, Paweł Adamowicz was handed a microphone. “Gdańsk is generous, Gdańsk shares, Gdańsk wants to be a city of solidarity,” said the Mayor. “I thank you so much for all of this, because you gave your money on the streets and squares of Gdańsk, for being volunteers. This is a wonderful time to share. I love you. Gdańsk is the most wonderful city on Earth. Thank you all!”

When he spoke his last words, there were 64 seconds left to the first stab of the knife. It was almost 20:00 hrs. The countdown to the Light began. Thousands of smiling people about, with hands up in the air, with sparklers or mobile phone lights. Hundreds and thousands of voices:

Ten!

Nine!

Eight!

The countdown came with blazes and smoke from the fireworks onstage.

Seven!

Six!

Five!

Four!

Three!

Some of those who were there saw a silhouette of a man who quickly came across the stage. He looked like a stagehand hurrying to fix something.

Two!

One!

Nooow!

The mayor stood happy, holding a sparkler in his hand. And then this man ran into Paweł Adamowicz and knocked him over. That’s what it looked like at first.